THE GRAND THEFT OF SABAH: Why We Must Stop Blaming the Poor for the Greed of the Rich

I. Introduction: The Narrative of "The Cheap Sabahan"

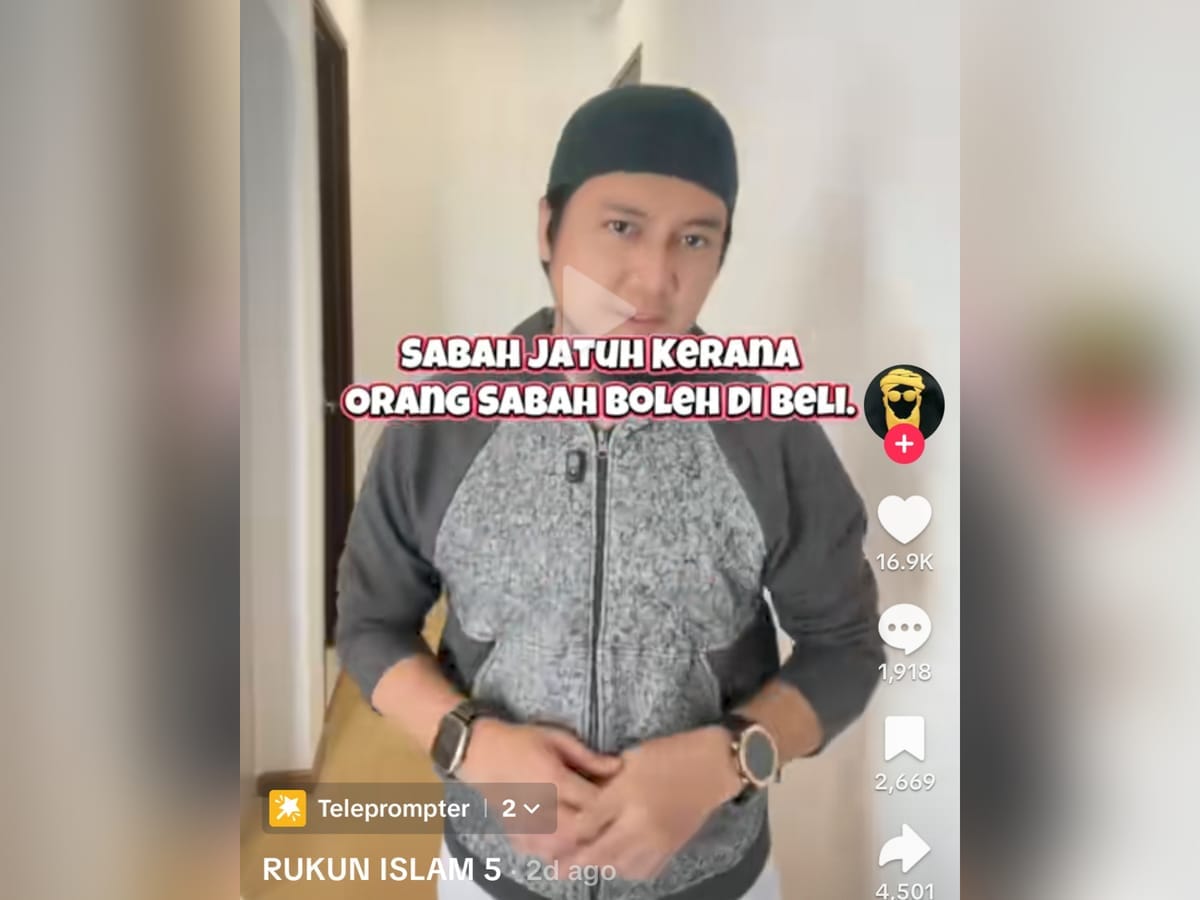

There is a video circulating on social media right now. You might have seen it. It features a man in a kopiah, speaking with the cadence of a preacher, lamenting the fall of Sabah. His thesis is simple, seductive, and fundamentally dangerous:

"Sabah fell because Sabahans can be bought."

He points to the RM50 or RM100 handouts given during election seasons. He scolds the rakyat for selling their dignity. He mocks the public outrage over the tragic Zara case, implying that our anger is misplaced if we are willing to "close our eyes" for a bit of cash. He paints a picture where the politician giving the bribe and the villager taking it are partners in crime—equally sinful, equally responsible.

This is a lie.

It is a comfortable lie for the elites, and a devastating lie for the working class. It is a narrative that shifts the moral burden from the powerful oppressor to the powerless oppressed.

This report is a rebuttal. It is an exposure of the "Clientelism" trap, the misuse of religious guilt, and the economic reality that proves Sabahans are not greedy—they are hostages.

II. The Economics of Control: "Starving the Fish"

To understand why an RM50 bribe works, we must first ask: Why is RM50 so valuable in a state as rich as Sabah?

Sabah is not poor. Sabah is a treasure house. We have:

- Oil and Gas: Billions in revenue pumped out of our waters.

- Timber: Decades of logging that stripped our forests.

- Minerals: The new gold rush (gold, copper, rare earth elements) currently sparking scandals.

- Tourism: A world-class destination.

Yet, despite this immense wealth, Sabah consistently records the highest poverty rates in Malaysia. Why?

The Strategy of Dependent Poverty

This is not an accident; it is a political strategy known as Patronage Politics or Clientelism.

If a government builds good roads, provides clean water, ensures high wages, and creates a robust education system, the people become independent. An independent voter does not need a politician to survive. They can vote based on policy, ideology, and performance.

However, if you deliberately withhold development—if you keep the roads broken, the water taps dry, and the wages low—you create a population in a constant state of need.

The Trap: The corrupt politician creates the poverty during their 5-year term. They "starve the fish." Then, during the election, they appear as "saviours" with a small bag of rice or RM50 cash.

Blaming a Sabahan for taking that money is like breaking a man’s legs, stealing his wheelchair, and then mocking him for accepting the crutches you sold him. The video criticising the people ignores the fact that the hunger was engineered to make the bait irresistible.

III. Spiritual Gaslighting: Distorting Religion to Shield the Powerful

One of the most insidious aspects of the viral video is its use of religious language to silence dissent. This is Spiritual Gaslighting.

The speaker references the Islamic concept of Risywah (bribery), implying a blanket ruling that "the giver and the receiver are both in Hellfire." By applying this equally to a billionaire Minister and a starving villager, he commits a grave theological and moral error.

The "Equal Sin" Fallacy

Scholars of Islamic jurisprudence have long debated the nuance of bribery when it involves oppression (Zulm).

1. The Oppressor (The Taker):

When a politician takes a bribe (or creates a system of bribery) to grant a mining license, destroy a forest, or pervert justice, they are committing a heinous sin. They are betraying the Amanah (trust) of millions. This is greed.

2. The Oppressed (The Giver/Receiver of "Survival Money"):

What about the person who pays a bribe to get their water connected? Or the voter who takes RM50 to feed their family?

Prominent scholars, including Imam Taqi al-Din al-Subki (in Fatawa al-Subki) and Imam Al-Suyuti, have made a critical distinction. They argue that if a person is denied their rightful due (sustenance, safety, rights) and is forced to participate in a corrupt system just to access those rights:

- The sin falls entirely on the receiver (the oppressor/official).

- The giver (the victim) is considered to be acting under Darura (necessity) or coercion.

By ignoring this distinction, the speaker in the video protects the corrupt elite. He tells the poor that their survival instinct is a sin, effectively shaming them into silence while the leaders continue to loot the state.

IV. Grand Corruption vs. Survival: The Scale of the Crime

We must contextualise the "Mineral License Scandal" mentioned in the video.

The allegations currently rocking Sabah involve assemblymen discussing bribes worth hundreds of thousands or millions of Ringgit. These are exchanges made in air-conditioned rooms, involving contracts that will strip Sabah of its natural resources for generations.

This is Grand Corruption. It robs the state of:

- Future revenue (that could build schools).

- Environmental safety (causing floods and pollution).

- Public trust.

Contrast this with the "corruption" of the villager taking RM50.

- The Politician: Steals the future to buy a third luxury car.

- The Villager: Accepts a crumb of their own stolen wealth to buy rice.

To equate these two actions is absurd. It is a false equivalence designed to make the ordinary citizen feel "dirty," so they don't feel righteous enough to demand justice.

"The people of Sabah are not 'cheap' for taking RM50; they are desperate because their immense wealth was stolen by the very people offering the bribe. The sin belongs to the one who hoards the state's wealth, not the one trying to survive the famine they created."

V. The Zara Case: Do Not Dismiss Our Rage

The video mocks the "Justice for Zara" movement, suggesting that people are hypocrites for caring about a specific tragedy while ignoring corruption.

This is a deflection tactic. The anger over the Zara case—and other injustices against our youth—is connected to corruption.

- Why are our campuses unsafe?

- Why is our infrastructure failing?

- Why are our social services underfunded?

Because the money was stolen.

Dismissing the people's grief as "hypocrisy" is cruel. It tells the rakyat that they are too "corrupt" to deserve justice for their children. We must reject this. We can be angry about the RM50 bribery AND be furious about the loss of life. They are symptoms of the same disease: a leadership that does not value Sabahan lives.

VI. Conclusion: Reclaiming the Narrative

We need to stop accepting the label of the "Lazy Sabahan" or the "Easily Bought Sabahan." These are colonial-era stereotypes repurposed by modern politicians to justify their neglect.

To the People of Sabah:

- Do not internalise the guilt. If you took money to survive, that is on them, not you. You are recovering a tiny fraction of what is yours.

- Recognise the trap. Understand that they keep you poor on purpose. The RM50 is not a gift; it is a leash.

- Reject the "Equal Sin" narrative. You are not the same as the man stealing millions. Your struggle is for survival; theirs is for excess.

To the Activists and Youth:

We must shift the spotlight. Every time a narrative emerges blaming the "stupid voters," we must redirect it to the "predatory leaders."

- Do not ask: "Why did the voter take the money?"

- Ask: "Why has the state been kept so poor that RM50 determines an election?"

Sabah will not rise by shaming the hungry. Sabah will rise when we stop feeding the hand that starves us.

#SabahBangkit #StopVictimBlaming #JusticeForSabah #NotCheapJustRobbed

What Can You Do Next?

If this report resonates with you, consider the following steps:

- Share the counter-narrative: When you see videos blaming the poor, comment with the "Broken Legs and Crutches" analogy.

- Educate on "Starving the Fish": Help your family and elders understand that the poverty they face is a political tool, not a natural disaster.

- Demand Policy, Not Handouts: In the next election, ask candidates for their long-term economic plans, not just what they can give you today.